In 2022, Jason Liu was exactly where most chefs dream of being. His Beijing restaurant, Ling Long, had earned a spot on Asia’s 50 Best list. The reservations were steady. Critics were listening. Financially and reputationally, he was on the rise. But instead of capitalising on the momentum, Liu did the opposite: he shut everything down for a year and vanished.

He spent the following twelve months crisscrossing China with nothing but curiosity and an empty stomach. Purpose? To find the soul of Chinese cooking. And he did.

That experience translated into Ling Long Shanghai, which opened in March 2023 and immediately took over the country.

Thirteen months later, it sits at No. 27 on Asia’s 50 Best Restaurants, higher than its Beijing sibling, with a Michelin star and a reservation list that stretches months ahead.

The Artist’s Canvas

Liu’s path to culinary mastery began at sixteen when most teenagers were still figuring out their weekend plans. He started at Grand Hyatt Taipei while simultaneously attending Taiwan Kai-Ping Culinary School, working his way up through Taipei’s finest establishments—Café Bellini Dunnan, Paris 1930, and eventually his own restaurant, Bistro 3, where he served as chef and owner.

His foundation was built on French technique, the kind of precise, methodical approach that creates perfect mother sauces and flawless knife work. But something deeper was calling him.

After opening Ling Long Beijing in 2019 to critical acclaim, Liu realised he needed to understand his own culinary identity before he could truly express it.

“If I weren’t a chef, I would be a painter,” Liu shared during his conversation with That’s magazine. “As I’ve grown, all that has changed is the canvas: from paper to the dinner plate. Like a painter, I allow my surroundings to inspire me, building imagery in my mind to transform elements of the city around me into what I serve.”

This artistic sensibility drives everything Liu creates. Where other chefs might focus on technique or trend, Liu approaches each dish as a piece of visual and emotional storytelling.

Two Cities, Two Philosophies

When Liu decided to open Ling Long Shanghai, he faced a choice that would define his career. He could replicate his Beijing success or create something entirely new. He chose revolution.

“I knew I wanted to open Ling Long in Shanghai right away, although I needed first to overhaul the entire menu offered in Beijing for the Shanghai location, so it would include 90% new dishes, allowing repeat guests to enjoy a totally different experience between the two cities,” Liu explains.

The differences between his two restaurants reveal Liu’s evolution as a chef and philosopher. “Ling Long Beijing is more feminine, showcasing traditional dishes as the prototype, or jumping off point for innovation, while Ling Long Shanghai really hones in on the combination of xian and imagination. Just like the city itself, the Ling Long in Shanghai is boundary-less.”

What Happened Next

The first thing you notice about Ling Long Shanghai isn’t the food. It’s the beehive.

No, really. There’s a beehive on your table, complete with buzzing sounds and the faint smell of honey. It’s made of real beeswax, and it’s sitting next to what looks like a tree branch but is actually litsea bark that you’re supposed to scrape onto your fish.

Welcome to Jason Liu’s world, where nothing is quite what it seems and everything is exactly what it needs to be.

This is Chinese fine dining, but not as anyone has done before. Liu has taken the rulebook and turned it into origami. The result is something that shouldn’t work but absolutely does, something that feels both ancient and completely modern, like discovering a secret room in a house you thought you knew.

The Waldorf Experiment

Ling Long Shanghai occupies a prime position in the Waldorf Astoria on the Bund, a location that reflects Liu’s ambitions. The restaurant seats just thirty diners across eight tables and two private rooms, with a single seating each evening. This intimacy allows Liu to orchestrate each meal as a complete sensory experience.

The dining room feels like stepping into a Chinese painting that’s been given life. Crimson and onyx walls, white tablecloths, and art that seems to shift in the gentle lighting. However, the real performance happens in the open kitchen where Liu conducts his team with quiet authority. There’s no shouting, no chaos. Just precision and purpose.

What strikes you about Liu is how different he is from the stereotypical celebrity chef. He speaks softly, moves deliberately, and lets his food do the talking. At 28, he’s already collected more awards than most chefs see in a lifetime, but he wears them lightly. When he talks about his craft, it’s with the reverence of someone who understands he’s part of something much larger than himself.

The Language of Xian

Liu’s menu revolves around a single concept: xian. It’s one of those Chinese words that doesn’t translate neatly into English. Umami comes close, but xian is deeper than that. It’s freshness, it’s the essence of an ingredient, it’s that moment when a flavour hits your palate and you understand something you didn’t know you were looking for.

Take the signature broth made from preserved chicken leg and clam. It arrives in a pristine white bowl, crystal clear, looking almost too delicate to disturb. But that first spoonful hits you with the force of recognition.

This is comfort food distilled to its essence, elevated but never pretentious. It tastes like something your grandmother might have made if your grandmother happened to be a culinary genius.

The Story on Every Plate

Every dish at Ling Long tells a story, but Liu never hits you over the head with the narrative. The Tung Feng fried chicken arrives with a reproduction of an old hotel menu. The chicken is perfect, crispy skin giving way to impossibly tender meat stuffed with preserved vegetables.

But the real punch comes when you realise this is Liu’s tribute to the Tung Feng Hotel that once occupied this very space, the same hotel that housed China’s first KFC. It’s playful and profound at the same time.

The smoked drunken prawn comes swimming in Shaoxing yellow wine, the alcohol lending a complexity that builds with each bite. The braised eel looks like pork belly, tastes like childhood, and somehow manages to be both familiar and completely surprising. These aren’t fusion dishes in any conventional sense. They’re cultural conversations happening on a plate.

Liu’s Shandong Wagyu comes with oyster sauce made the old way, with an abundance of actual oysters rather than the synthetic stuff most restaurants use. It’s a small detail that speaks to a larger philosophy. Liu isn’t interested in shortcuts or approximations. He wants the real thing, even if it takes eight months to age his own parmesan or requires him to source honey from specific bee species.

The Sweet Madness

If the savory dishes establish Liu’s bona fides, dessert is where he reveals his sense of humor. The Chinese honey course arrives with that beehive we mentioned, complete with sound effects. It’s theatre, sure, but it’s a theatre in service of flavor. The combination of sour honey and dark honey from black bees creates a complexity that justifies all the pageantry.

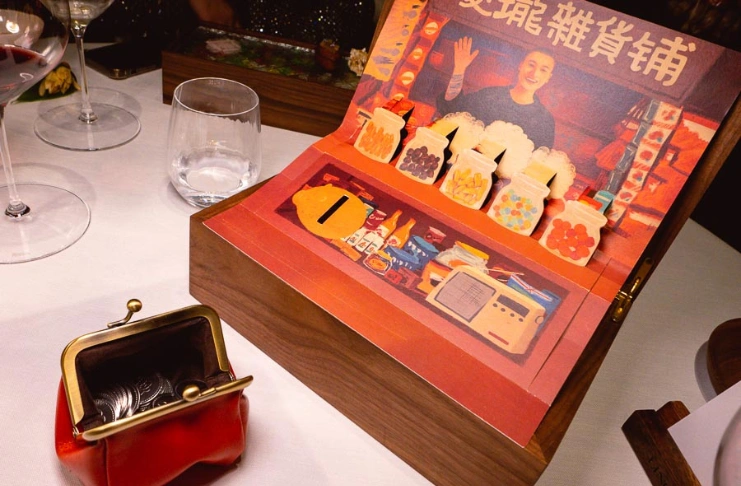

The finale brings out the candy shop. Literally, a wheeled cart arrives with what looks like a miniature store, complete with glass jars filled with petit fours and a coin-operated music box. Insert a coin, and the whole thing comes to life with circus music and the smell of childhood candy stores.

By this point in the meal, you’re not even surprised. You’ve been on Liu’s journey for two hours, and you trust him completely.

The Larger Picture

Liu’s success at Ling Long Shanghai represents something bigger than one restaurant doing well. It’s proof that Chinese cuisine can evolve without losing its soul, and that tradition and innovation aren’t opposing forces but dance partners.

In a culinary landscape often dominated by Western techniques and aesthetics, Liu has created something distinctly Chinese while remaining completely accessible to international diners.

Indeed, the numbers tell part of the story. However, the real measure of Liu’s success is in the way diners talk about the experience afterward. They don’t just describe the food. They describe the journey, the story, the way it made them feel.

Liu’s vision for Ling Long is ambitious but simple: “I hope this brand will continue to live and evolve on its own, becoming a benchmark in the Chinese dining scene.” Given what he’s accomplished in just over a year, this seems less like hope and more like inevitability.